My pacing practice

What is pacing?

After getting a Long Covid or ME/CFS diagnosis (or any "energy limiting" condition), you were likely recommended "pacing" to organize your everyday life. But what is pacing exactly?

Pacing is an energy management strategy that balances rest and exertion in order to limit symptoms increases (officially called Post-Exertional Malaise or PEM). It sounds simple, but if you've been practicing pacing, you know how hard it is.

This concept is very important because it's key to recovery. But I'd like to show you that there are several ways of practicing pacing.

In sports, we know that recovery time is necessary after training in order to make progress. In agriculture, fields are left fallow so the soil can regenerate after intensive crops.

All living beings need cycles, even when they are in good health, because it is what makes life sustainable.

My first experience with pacing

Spoiler alert: not great 😅

In the beginning of my journey, I applied the rules of "strict" pacing.

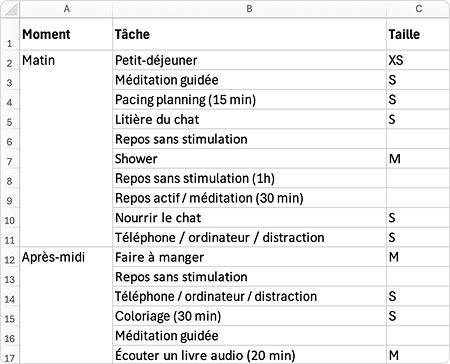

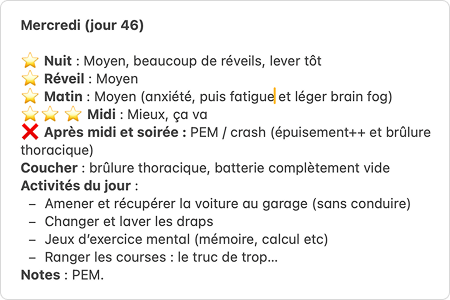

- Evaluating my energy envelope (also called "baseline")

- Sizing activities

- Planning my days / weeks, with activity and rest phases

- Using a timer and stopping any activity as soon as symptoms arise

- Tracking my symptoms in a journal and flagging "faulty" activities

Here's what it looked like for me:

This very structured approach shows good results for some people. If it works for you and feels right, that’s great! But for me, it was a bit of a disaster. 😅

This approach reinforced all of my toxic patterns: hyper control, hyper vigilance, fear of failure, guilt, and anxiety. Instead of helping me, it reinforced the alert state of my nervous system and made my symptoms worse overall.

The dominant narrative that you can “permanently damage your baseline” was also very harmful for me: when there’s no longer any room for mistakes, how can you keep living...? Such a terrifying message wasn't helpful for me, especially since stress itself objectively makes this illness worse.

Some form of pacing is still necessary, both to stabilize the condition and to make progress. The good news is that there are other ways to practice it, maybe better suited for people who have anxiety.

My own approach to pacing

My approach is now oriented towards safety and progress, rather than symptom management. It's based on listening to my body, intuition, and common sense.

I stopped planning my days in detail and reduced tracking a lot (of symptoms, of heart rate, of time or steps...).

- Each day, I let my body and intuition guide me in the activities I'm able to do, without pushing too far, but without anticipating disaster.

- If symptoms show up: I welcome them, slow down, and give myself rest and regulation activities.

Being in the present moment and adjusting in real time stopped my anxiety: It’s a gentle way of accepting my current limits, which signals to my brain that I'm safe. This pacing approach created a virtuous cycle for me, and allowed me to start progressing.

More details on my process in this article.

Changing my inner dialogue when I have symptoms was also extremely useful.

I no longer use words like "crash" or "PEM" (post-exertional malaise). They are too heavy and guilt-inducing. I prefer to talk about "setbacks" or "adjustment periods".

I no longer see my symptoms as punishment. When we start to make progress, it’s normal and inevitable to experience at least a few symptoms. They're a necessary component of progress cycles.

Example:

- I don't say: "I overdid it, it's all my fault. 😣",

- I prefer: "I did great things today! Symptoms are here, temporarily. I'll get some rest and regulation. 😌"

But how can I offer myself good rest?

Rest, yes... but quality rest!

You get the idea, you’ll need phases of rest and repair in order to progress. But what does “rest” really mean? Of course, rest needs to be adapted to your current capacity, but it doesn’t always mean "lying down with no stimulation".

Here are the 7 types of rest according to Dr. Saundra Dalton-Smith:

- Physical: sleep, naps, gentle stretching, yoga, massage.

- Mental: taking breaks (especially from screens), guided meditation, mental relaxation.

- Sensory: closing your eyes, isolating yourself from noise, cooling down. For people in severe states, an eye mask and noise-cancelling headphones can help rest the senses.

- Creative: connecting with nature and the beauty of the world, listening to music, doing playful or artistic activities.

- Emotional: expressing your emotions, journaling, talking with a trusted friend.

- Social: spending time alone, or surrounding yourself with safe people with whom you can be 100% yourself.

- Spiritual: connecting to something greater and letting go. For me, it simply meant trusting the Universe. I don’t believe in God, but I discovered that I had faith in nature.

Bonus: Rest through changing activity

Sometimes, simply changing activity can help you regulate without going through "total rest". For example, after a long time in front of a screen, taking a breath outside can give me more energy than lying down on my bed. Of course, the idea is not to force yourself, but to ask your body what it needs at any given moment.

Note: When I was very severe, I needed to spend 95% of the time lying down without stimulation. But even in that state, working with my inner dialogue and focusing on small joyful things really helped. I share some ideas here.

Conclusion

Since I’ve been applying this gentle approach, my adjustment periods have become less and less frequent and intense. My overall capacity is improving. What matters for me is not avoiding symptoms at all costs, but listening to my body and my needs.

Pacing remains very challenging, I know. Many of us have to unlearn lifelong habits, as society often encourages us to always push through… But sometimes, we need to accept to slow down to allow our bodies to heal.

Note: The severity of my condition led me to lose my job, and I don’t have children. In the midst of difficulty, I was fortunate in a way: the illness forced me to focus 100% on myself and my needs.

If you do have obligations, be extra gentle with yourself and ask for help. You deserve to have the time to take care of yourself.

If you want to keep reading, you may find helpful tips in the post about how I went through each level of severity with this illness.