Getting better: What activity expansion looks like

You may find it helpful to read the post about the signs you are healing first, before diving into this one.

Once you feel more stable thanks to regulation tools and pacing, your energy will slowly return, and you’ll naturally start expanding your activities.

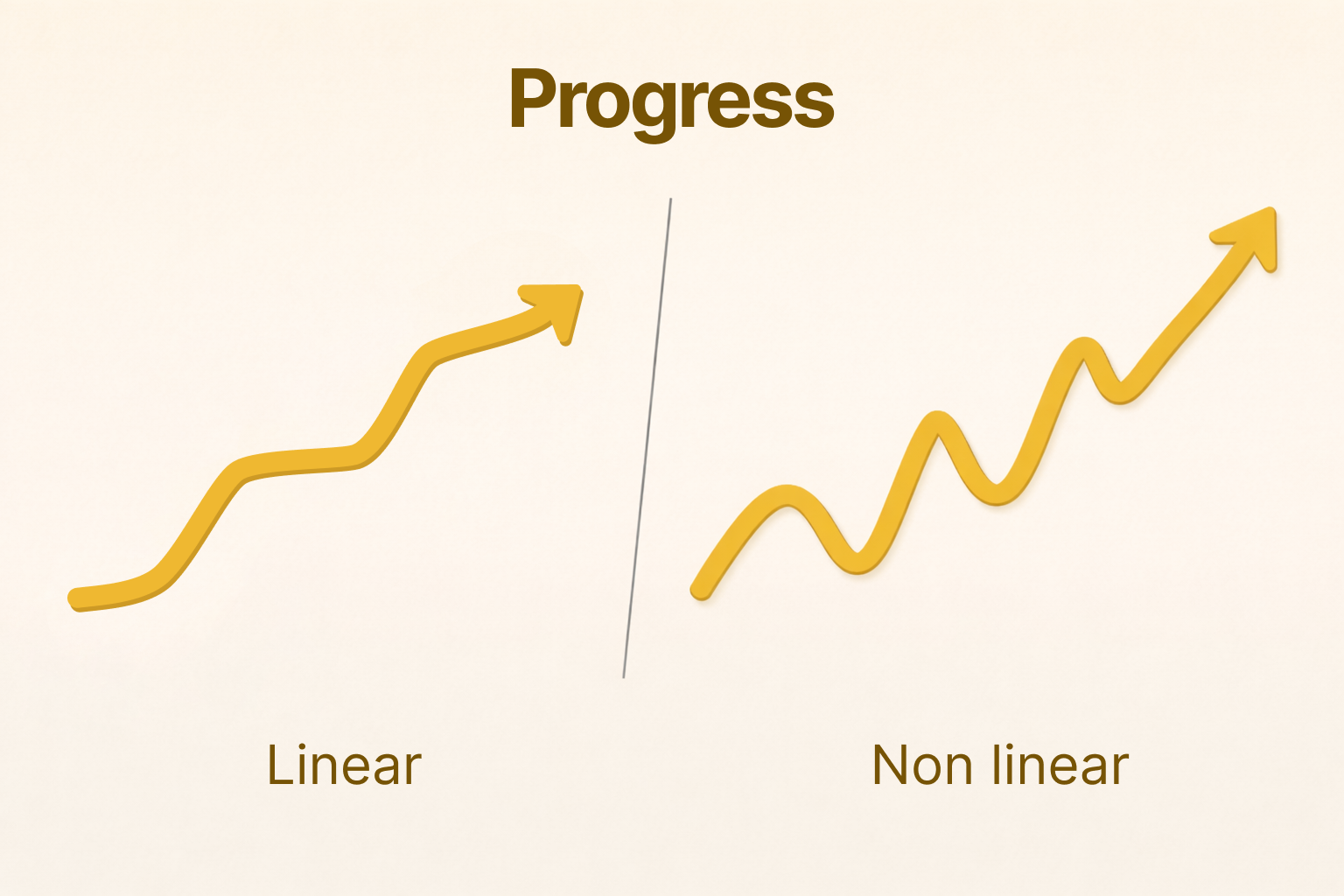

There are a lot of narratives around activity expansion, but they all agree on the fact that progress is gradual and non-linear.

In this post, I’ll share how it unfolded for me: how I approached deconditioning, my expansion rules, and concrete examples from my own experience.

I- Managing deconditioning

Physical deconditioning and muscle loss is indeed a consequence of energy-limiting conditions, and yes, they are real issues.

As patients, we receive mixed messages about this all the time, from doctors, relatives, or patient associations:

"You should avoid deconditioning.

Your body needs movement to be healthy.

But you should never push through your symptoms!

So you should rest more!" 🤷♀️

Finding the right balance with movement is difficult. When I was bedbound, I saw my body changing, and I felt powerless and scared.

Back then, my coach told me a few things that helped me tremendously manage my fears:

- Deconditioning is real when we don't move enough, but it doesn't happen that fast, and it is reversible.

- Worrying about deconditioning is not helpful. Movement is important, but with ME/CFS and similar conditions, forcing your body to move in a dysregulated state will make things worse.

- Pushing through is not the way out. Finding a path back to joyful movement in a regulated state is.

- Reconditioning happens naturally once you start moving again in a regulated state: first through daily-life movement, then with gentle exercise once you're ready.

II- My activity expansion strategy

1- My expansion rules

80% confident

When I feel like doing something, I ask myself:

- Do I feel safe and regulated right now?

- Do I feel 80–90% confident that I can do this?

If yes to both, then I’m in the right state to try.

Baby steps

Wherever you are in your recovery journey, don't focus on the final goal. Full recovery can feel impossible, because you're imagining everything a fully recovered person can do through the lens of your current state. Right now, only the next baby step matters.

No pressure

Specific goals, timelines, and tracking tend to reinforce hypervigilance and unrealistic expectations. Personally, I found they never helped.

Enjoy

During the activity, stay present and focus on enjoyment. Afterwards, celebrate!

Welcoming symptoms

If symptoms show up after an activity, it's not a failure, it's information about your nervous system's state. A slight increase in symptoms while expanding is expected and part of the process.

More details: managing setbacks and pacing.

2- Handling overwhelm

When you start expanding your capacity, the goal is not to do activities in "super hard mode", it's to make activities feasible again, within your current capacity. At first, use all the coping mechanisms that help reduce overwhelm, so you can focus on the activity itself, and the joy it brings.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of things I personally found helpful.

🧠 Reduce cognitive load

- Wearing noise cancelling headphones or earplugs

- Using an eye mask (for example during car rides, to reduce motion overwhelm)

- Wearing sunglasses and a cap

- Choosing calmer times for outings (fewer people, less stimulation)

💪 Reduce physical load

- Mobility aids (I used a wheelchair outdoors for a little over a year)

- Wearing comfortable clothes

- Finding ways to stay as reclined as possible (for example, adjusting car seats)

- Asking for help, so you can participate without carrying all the load

🧘♀️ Reduce emotional load

- Planning ahead to make the activity as predictable and stress-free as possible

- Bringing soothing objects (I used fidget toys, a small cushion, or a plush toy)

- Expressing your needs clearly (asking for breaks, stopping earlier, etc.)

- Choosing whether you feel safer alone or accompanied

(Being with a loved one can bring co-regulation; being alone can help you fully respect your rhythm. Do what feels safest.)

Not necessarily! Use coping mechanisms for as long as you need them, and respect your body's needs at each stage of recovery. But as you progress, you'll know intuitively when you are ready to let go of a coping strategy.

3- Examples from my own journey

Very gradual increases, relying on my body’s intuition, and taking (sometimes ridiculously) small steps were key in my progress.

🚶♀️ Starting to walk again

- I started by walking from my bed to the front door. I opened it, looked outside, breathed fresh air for a few seconds, went back to bed. Success!

- Then I sat outside in a recliner to get used to outside sounds.

- Then I took a few steps on my deck.

- Then I walked to my apple tree in the garden (about 20 steps). 🌳

- Then to my mailbox and back.

Slowly, I expanded my steps around my house, then around my block, then further. Walking slowly, mindfully, paying attention to my surroundings and to my breathing. Each time, I let my body take me where it felt safe to go.

🚗 Driving

- I started with short car rides as a passenger with my partner.

- Then I sat in my own car and played with the pedals and gear stick for a minute, without starting the engine.

- Then I simply started the engine to see how it felt.

- Then I parked the car just a few meters further away.

- Then I drove once around the block.

When I started driving further away, I sometimes needed to actively regulate myself during the ride, and I was able to bring my nervous system back to a state of safety.

🛒 Going back to the supermarket

This one was a challenge. Supermarkets have it all: strong lights, loud music, food smells, lots of people, waiting time, and interactions.

- First, I drove to the supermarket, just to have a look at it from outside, and went back home.

- Then, I entered the supermarket and left immediately.

- Then I went in, grabbed one item in the first aisle, and checked out (I remember it well, I picked lollipops for Halloween).

- Eventually, I was able to spend more time inside, slowly looking at products.

For me, each progress phase took months. I'm not saying that to scare you, some people do have quicker progress! But if it is slow for you too, it doesn't mean you are doing anything wrong.

III- About GET (Graded Exercise Therapy)

Many doctors still recommend GET. While it can be helpful for many conditions, it is not designed for ME/CFS recovery.

GET is based on a predictable, linear progression, whereas recovery from ME/CFS and similar energy-limiting conditions is non-linear and requires day-to-day adaptation based on the nervous system's current state. This doesn’t fit well with the traditional medical model of recovery.

On the path to recovery from ME/CFS, you may walk 1,000 steps one day, then only 50 steps the next, and then 2,000 steps a few weeks later—rather than 300 steps consistently every day. This is a non-linear form of progress.

I personally chose not to work with a physiotherapist, but this was an individual decision. Some people do benefit from more guided support. If you explore this route, look for someone who understands energy-limiting conditions and trust your gut to assess whether this person is a good match for you!

Remember: the goal is always to bring more safety and ease into activity, not more fear and hypervigilance.

Conclusion

This journey will test your resilience. But it can be seen as learning a skill. Because that's exactly what it is: your brain is relearning safety from scratch.

Any meaningful learning takes practice and many attempts (and failures). Each tiny win is proof that your body is able to heal.

You are doing incredibly difficult work, that very few people will ever have to do in their lifetime. Be kind to yourself.

I love this mantra that Jan Rothney cites in her book:

“If I did it once, I can do it again”

Member discussion